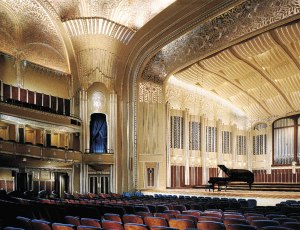

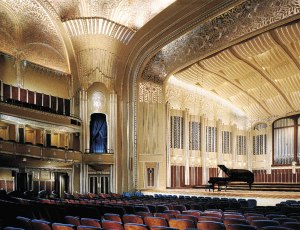

Eighty-two years might like a long time to live. For centuries, most humans didn’t make it that far, and even today, octogenarians are relatively few and far between. Those who remain live knowing that their days are numbered and struggle to hold on to life for just a little longer. Fortunately, I’m not expected to die any time soon. Indeed, my counterparts are notoriously long lived- the Musikverein in Vienna is nearly one hundred and fifty, and the Sheldonian Theatre at Oxford has nearly three hundred and fifty years under its belt. Despite the fact that I am not even middle-aged, it seems suitable that I should reflect upon the drastic changes I have experienced throughout my short lifetime.

When I was an infant, the love child of a grieving philanthropist, the players were good, but nothing special. It didn’t really matter- Cleveland finally had a band of its own, almost one hundred years after Vienna. And so I grew up, tolerating Sokoloff, Rodzinski, and Leinsdorf, listening as the musicians, paid peanuts but as good as any other American orchestra, grew accustomed to playing inside me. It was a happy childhood- the orchestra wasn’t awful. However, after Leinsdorf left during my teenage years to continue what would be a magnificent career, the musicians and I were in for a surprise.

Nikolai Sokoloff

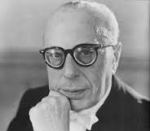

Like many teenagers, I had a persistent, nagging father figure who stubbornly guided me into shape. This figure was George Szell, and when he came to Cleveland, he knew that he had to make some changes. To begin with, he was hard on my players. The playing that had been sufficient for Sokoloff, Rodzinski, and Leinsdorf seemed second-rate to the Hungarian. From the very beginning of his tenure, he fired musicians who he felt did not fit and created an intimidating culture and pressure to be technically and musically perfect. He even fiddled with me, building the infamous “Szell Shell” inside me to improve my acoustics. Though I was wary and even afraid of “Dr. Cyclops” when he first arrived in Cleveland, I am glad he operated on my musical friends and me. Without him, the Cleveland Orchestra and I might have gone the way of an orchestra like the Baltimore Symphony- quite talented, but nobody’s first choice. Instead, he spent the twenty-odd years he had with the musicians turning them into the most precise ensemble in the world and me into one of the best-sounding halls. Though it was painful, I am grateful that he whipped us into shape.

George Szell

After Szell, the musicians stayed as good as ever, but the conductors weren’t as special as he was. Granted, they were able, but it was as if Szell had turned the orchestra and me from a Volvo into a Ferrari, and the new conductors were just good drivers. This Ferrari’s parts became more and more valuable as time passed: while during my infancy the hardworking players were paid enough to survive, today they are the performing arts’ aristocrats, earning more than my childhood friends could have dreamed about. I can’t say that I don’t mind being one of the orchestra world’s most well maintained cars, but I miss the glory days when Szell thrust Cleveland onto the international scene.

Though I have indeed matured throughout the years, a far more drastic shift has occurred in the audiences that hear the orchestra play. In the beginning, I was a privilege reserved only for the rich and famous; I even had a special entrance for chauffeurs to drop of guests of honor. For decades, nobody questioned that I was a valuable cultural icon. Money was not an issue. However, as time passed and fleeting popular music took over society and my most faithful patrons died, cash flow was choked off. Suddenly, management had to pursue options that twenty years before would have seemed inconceivable- playing with jazz and popular music stars, starting a shortened Friday night concert series with a dance party afterwards, aggressively pursuing young people with ten and twenty dollar ticket offers. In a place where tuxedos in the audience, not just on stage, used to be custom, guests began to show up in clothes as casual as t-shirts, shorts, and sneakers. Empty seats, once a rarity, became commonplace, especially during concerts of lesser-known programming. Indeed, one conductor even joked that the Orchestra would have to play Beethoven’s Ninth every year just to balance the budget! Though my situation is considerably better than that of someplace like Minnesota, it is uncomfortable being a young concert hall whose future is unknown.

There will always be the Musikverein, the Philharmonie, the Concertgebouw, and the Royal Albert Hall. A handful of classical musicians in Vienna, Berlin, Amsterdam, and London will always play. But will I always exist? Will I be shut down, abandoned, discarded? Will I live long? I dislike having to confront the questions about life that a human octogenarian might ask himself. I can only hope that the jeans and basketball shoes that stick out amongst my velvet seats signal a shift in the classical paradigm, not the beginning of the end. I can only hope that the culture that I have given the people during the past eighty-two years was not all for naught, and that my musical heart will continue to beat for many years to come.